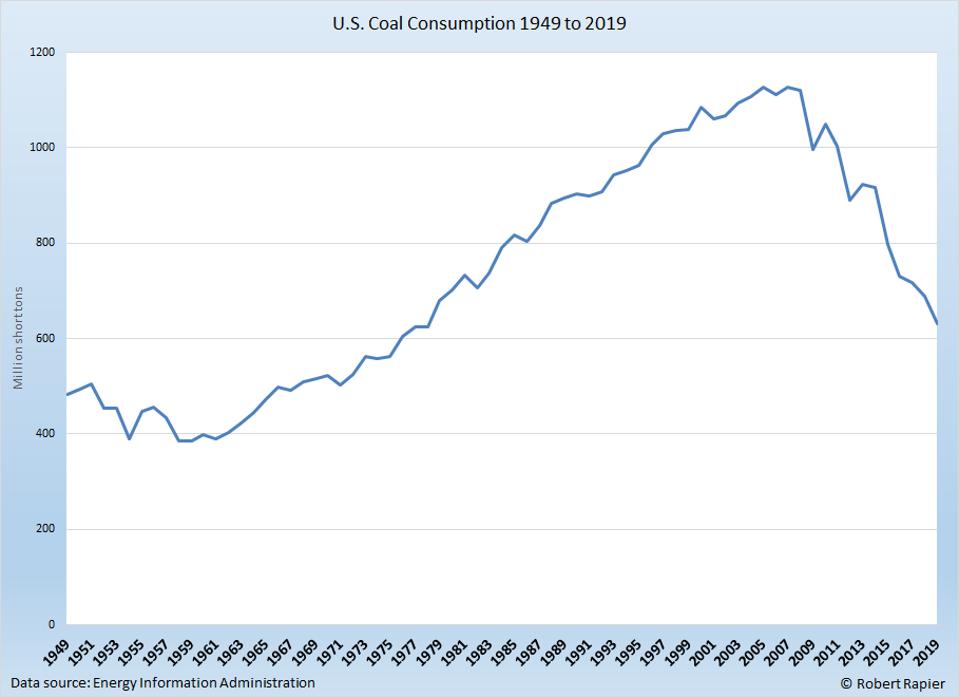

After a steady rise that lasted nearly 50 years, U.S. coal consumption peaked about a decade ago. Since the peak in 2007, coal consumption in the U.S. has fallen an astounding 44%.

There are two primary reasons behind coal’s death spiral. Both were aided by legislation aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

There are two primary reasons behind coal’s death spiral. Both were aided by legislation aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

The first was that the shale gas boom in the U.S. unleashed massive new supplies of cheap natural gas. This made it economical for power plants to switch from coal to natural gas. Power produced from natural gas has lower associated carbon dioxide emissions.

The second was tremendous growth in the availability of cheap renewables like wind and solar power. As the price of these renewables declined, they grew exponentially. Since 2007, consumption of renewable power in the U.S. has more than quadrupled. Consumption of renewable power in the U.S. rose by 349 terawatt-hours (TWh) from 2007 to 2018. Over that same span, power from natural gas increased by 696 TWh.

The Impact on Carbon Dioxide Emissions

The decline of coal has had a big impact on U.S. carbon dioxide emissions. Since coal’s peak demand year of 2007, carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. have fallen by 716 million metric tons. This is by far the largest decline of any country.

For reference, the 2nd leading country, the U.K., decreased carbon dioxide emissions by 176 million metric tons over that time span. At the same time, global emissions increased by 3.5 billion metric tons. The Asia Pacific region’s 4.0 billion metric ton increase in carbon dioxide emissions was partially offset by declines primarily in the U.S. and EU.

There are those who have suggested that oil will follow this pattern, and that oil’s decline will soon be at hand. The electrification of transportation is primarily expected to cause this decline.

I disagree.

Oil Isn’t Like Coal

First, while I do agree that electric vehicle (EV) growth will remain robust for many years, the turnover of the transportation fleet is a slow process. Many power plants were in a position to rapidly switch from coal to natural gas as legislation and economics made the switch appealing. They didn’t have to wait for the coal-fired plants to reach the end of their useful life. If they had, the transition would have been a much slower process.

We can look to a couple of examples to highlight the differences between oil and coal. Norway leads the world in the penetration of EVs. From 2009, Norway grew EV sales by triple digits for seven years. EV market penetration reached 5% in Norway in December 2016, and 10% less than two years later in October 2018. This is five times the new vehicle market share of EVs in the U.S.

But Norway’s oil demand has been slow to respond. According to the 2019 BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Norway’s oil consumption has actually increased over the past decade. In 2018, Norway consumed 234,000 barrels per day (BPD), 5% more than in 2017 and the highest annual consumption number on record.

The story is similar in the largest EV market in the U.S. California’s EV market share reached 4.8% in 2017, and surged to 7.8% in 2018. But data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) shows that California’s oil consumption has risen each year since 2012.

The California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA) did show a 0.4% decline in Net Taxable Gasoline gallons in 2018, but that followed a 10-year high gasoline consumption level in 2017.

China is the largest EV market in the world. EV sales in China were over three times those of the U.S., with EVs hitting a 4.2% share of all new vehicles sold in 2018. Meanwhile, China’s oil demand grew 5.3% last year. This was a new all-time high above 13 million BPD, and above the 10-year average annual growth rate of 5.1%.

There are a couple of reasons behind the lack of a major oil response. Population growth and low gasoline prices have helped push the total number of annual vehicle miles traveled in the U.S. to an all-time high. That helps offset — and in some cases can completely offset — the impact from an increase in the number of electric vehicles on the roads.

Conclusions

At some point, oil demand will begin to decline in response to EVs. But global oil consumption grew by 1.5% in 2018 — above its 10-year average annual growth rate of 1.2%. Oil demand grew in the U.S. by 2.5% to the highest level since 2007.

Norway’s oil demand had been pretty flat over the past decade before surging last year, and there are some signs that California’s oil demand may be slowing. But despite rapid penetration of electric vehicles, there hasn’t been much — if any — reduction in oil demand.

Given the leading edge examples that we have of Norway, California, and China it seems pretty clear that oil won’t follow coal’s trajectory.

Follow Robert Rapier on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.