What is the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR)? What are the implications of depleting the SPR, which the U.S. has been doing now since 2016? Further, what has been the impact of the rapid drawdown of the SPR that has taken place this year? Let’s discuss.

SPR 101

In December 1975, with memories of gas lines fresh on the minds of Americans as a result of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, Congress established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The law was designed “to reduce the impact of severe energy supply interruptions” such as that caused by the embargo.

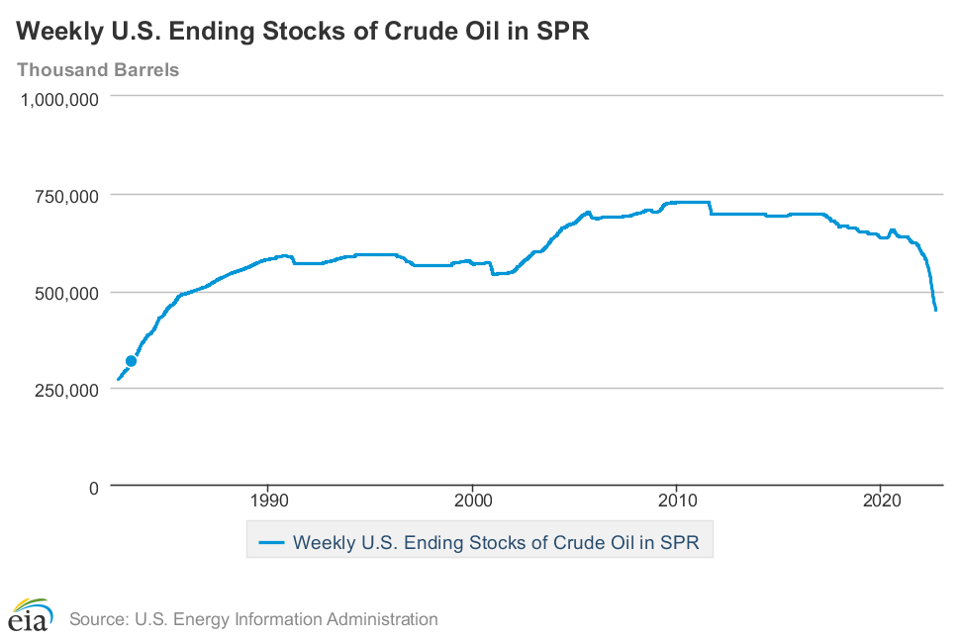

Over time the U.S. government began to fill the reserve. At its high point in 2010, the level reach 726.6 million barrels. Since December 1984, the level has never been lower than 450 million barrels — until now.

Some have noted that the SPR is less important than it once was. U.S. shale oil production has enhanced American energy security and lessens the importance of the SPR by reducing our dependence on imports.

Some have noted that the SPR is less important than it once was. U.S. shale oil production has enhanced American energy security and lessens the importance of the SPR by reducing our dependence on imports.

Consider that in 2005, the U.S. imported 10.1 million barrels per day (BPD) of crude oil, of which 4.8 million BPD (~48%) came from OPEC. The SPR contained 685 million barrels. With the U.S. importing 10.1 million BPD of crude oil at that time, that was enough oil to cover 68 days of supply.

In 2021, the U.S. imported 6.1 million BPD, of which only 800,000 BPD came from OPEC. More importantly, a lot of that imported oil was refined and re-exported as finished products. Net imports of U.S. crude oil and finished products were actually -62,000 BPD (i.e., the U.S. was a net exporter).

Thus, one could certainly argue that the SPR is of less strategic importance than it once was, and that perhaps we no longer need a 700 million barrel reserve of oil.

President Biden Taps the SPR

On March 31, 2022 — in an attempt to fight higher oil and gasoline prices — President Biden announced the release of one million barrels of crude oil a day for six months from the SPR.

I remember when I first heard about it, I thought “Wow. That’s a lot.” In fact, I noted in interviews at the time that this level of release would likely help stem oil prices — at the risk of depleting our insurance policy in case of a supply disruption.

Consider that with the U.S. producing 12 million BPD, an extra one million BPD pushes total U.S. “supply” (which isn’t sustainable, because it relies on depleting the SPR) back up to the all-time pre-Covid high of 13 million BPD.

Politics of the SPR

Ultimately, drawing down the SPR was a political decision. Think about it. An administration that has frequently emphasized the importance of reducing carbon emissions is trying to increase oil supplies to bring down rising oil prices — which will in turn help keep demand (and carbon emissions) high.

But even though the Biden Administration wants to address rising carbon emissions, high gasoline prices cause incumbents to lose elections. So, they try to tame gasoline prices even though it contradicts one of their key objectives of reducing carbon emissions.

The SPR has now been depleted since President Biden took office from 640 million barrels to 450 million barrels. This depletion is consistent with recent history. Historically SPR volumes tended to grow during Republican administrations and to fall during Democratic administrations. That pattern has held true since 1980.

Presidents Clinton and Obama both used the SPR to try to ease high gasoline prices around election time, while Republican presidents (until Donald Trump) added to the SPR. President Trump drew down about 10% of the SPR during his term.

President Biden has announced steps to replenish the SPR, “likely after FY2023”, and in my opinion most likely after the 2024 elections. President Biden’s gamble to deplete the SPR in order to fight high oil prices may not hurt him at all. Of course, if for some reason we had a true supply emergency and found ourselves needing that oil, it would be looked upon as a terrible decision.

Follow Robert Rapier on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.