This is the sixth and final article in a series on the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020. The Review provides a comprehensive picture of supply and demand for major energy sources on a country-level basis. Previous articles covered overall energy consumption, petroleum supply and demand, natural gas, coal, and renewable energy.

Today, I want to conclude with global carbon dioxide emissions.

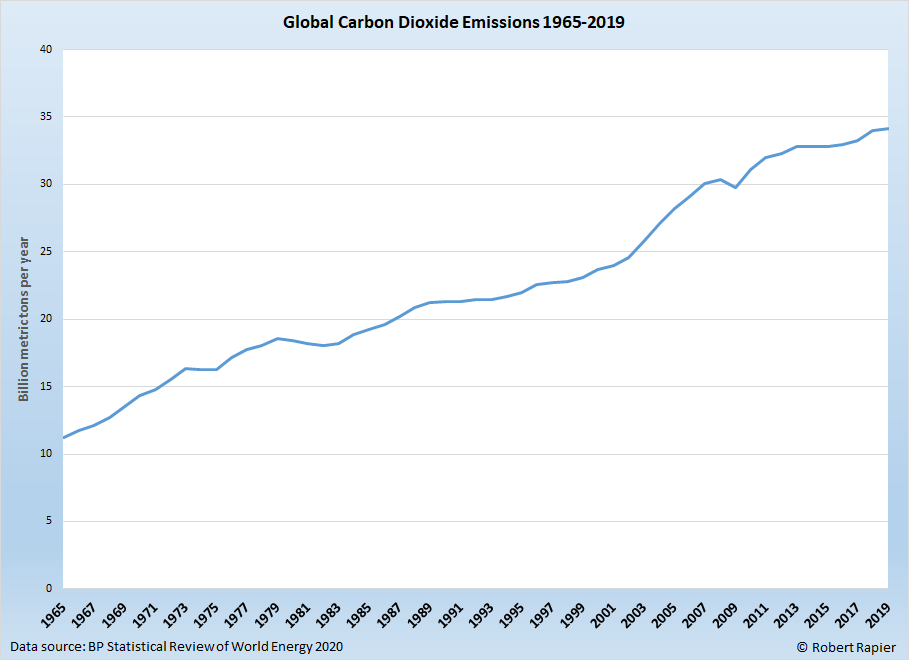

The previous article highlighted the explosive global growth of renewable energy. However, overall energy demand has been so great that fossil fuel consumption has also continued to grow. That means that global carbon dioxide emissions are still rising. In 2019, carbon dioxide emissions reached an all-time global high for the fourth consecutive year.

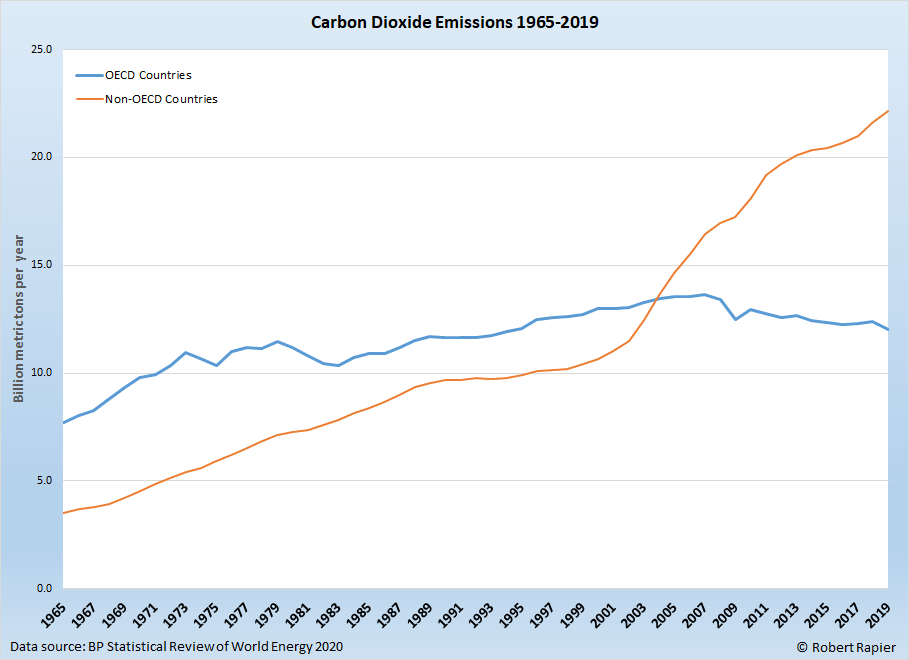

There is a huge disparity between carbon emissions of developed countries and those of developing countries. The 37 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are high-income countries generally regarded as developed countries. Carbon dioxide emissions in these countries have been in decline for over a decade, and are at approximately the same level they were at 25 years ago.

Non-OECD countries, on the other hand, have seen an explosion in the growth of carbon dioxide emissions. There are two primary reasons for this disparity. One is that the OECD countries achieved their development on the back of coal, which is now being phased out. But the non-OECD countries are currently developing by using coal, and that is driving up their carbon emissions.

Non-OECD countries, on the other hand, have seen an explosion in the growth of carbon dioxide emissions. There are two primary reasons for this disparity. One is that the OECD countries achieved their development on the back of coal, which is now being phased out. But the non-OECD countries are currently developing by using coal, and that is driving up their carbon emissions.

The second major reason is that the majority of the world’s population lives in developing countries. Even though per capita emissions in these countries is low compared to developed countries, incomes are increasing and the middle class is growing. Thus, a large population of people that is slightly increasing per capita emissions is having a large overall impact on global emissions.

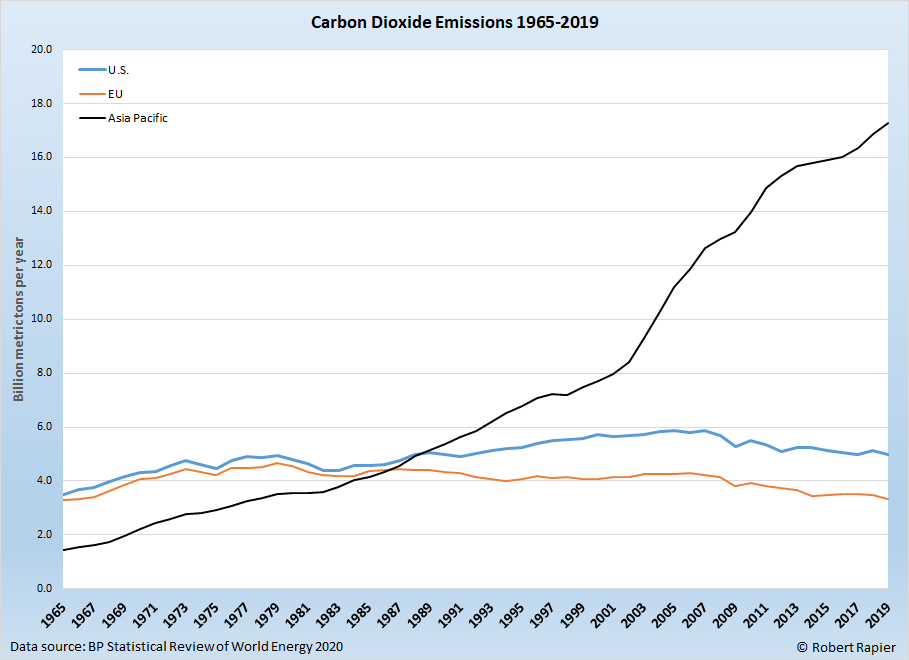

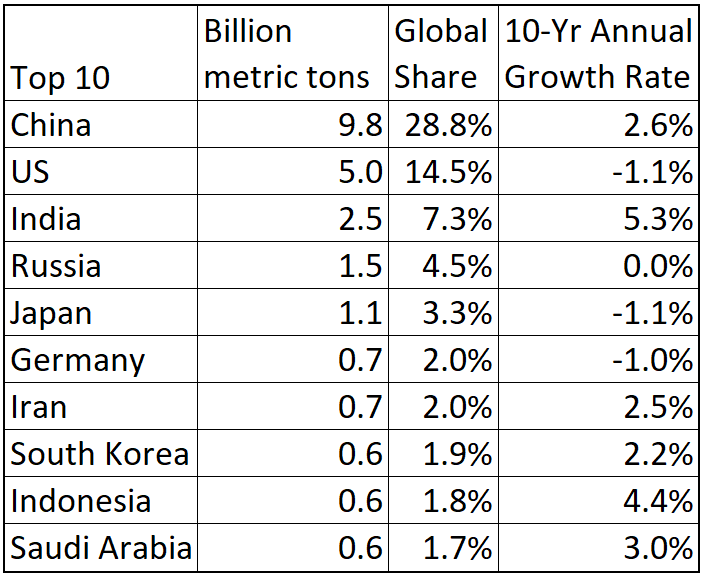

Consider that 4.3 billion people live in the Asia Pacific region. That represents 60% of the world’s population. The billions of people in the Asia Pacific region that are slowly increasing their per capita carbon dioxide emissions have driven the region’s emissions to more than double the combined emissions of the U.S. and the EU.

It’s not just Chine and India either. Multiple Asia Pacific countries are both among the largest carbon dioxide emitters and are among the leaders in emissions growth.

It’s not just Chine and India either. Multiple Asia Pacific countries are both among the largest carbon dioxide emitters and are among the leaders in emissions growth.

This issue illustrates why it has been so difficult to curb global carbon dioxide emissions. Developed countries can point to countries like China with large overall emissions as a problem, but China can rightfully note that the per capita emissions of its citizens is low relative to the West.

This issue illustrates why it has been so difficult to curb global carbon dioxide emissions. Developed countries can point to countries like China with large overall emissions as a problem, but China can rightfully note that the per capita emissions of its citizens is low relative to the West.

The average Chinese citizen emitted 7.0 metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2019. That was less than half the 15 tons emitted by the average American. Despite its rapid growth rate India only emitted 1.8 metric tons of carbon dioxide per person.

Hence, debates over curtailment of carbon dioxide emissions often reach an impasse over these issues. It is hard for developed countries to lecture China and India about curbing emissions when our own per capita emissions are so high.

But one thing is certain. Global carbon dioxide emissions growth has been driven higher by developing countries for the past 20 years. Current trends suggest that will continue to be the case. So the world doesn’t stand a chance of curbing carbon dioxide emissions without figuring out a way to stop emissions growth in these populous developing countries.

If there’s a silver lining in the data, it’s that the 0.5% global emissions growth rate last year was less than half the decade-long annual average of 1.1%. Further, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, emissions are almost certain to decline this year. Longer term, it’s going to require more phasing out of coal, and continued exponential growth in the adoption of renewable energy.

Follow Robert Rapier on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.