Introduction

While I believe that a global peak in worldwide oil production presents an unprecedented challenge to the way most of the Western world lives our lives, I do not believe that world oil production has yet peaked. However, in looking at the new oil capacity that is scheduled to come online, and contrasting that with the projected demand growth, it became clear to me over a year ago that demand was going to rise faster than new supply could come online.

This prompted me to propose the idea of “Peak Lite.” It is “peak”, because the symptoms will mostly manifest themselves as those of a true production peak: Not enough supply to meet demand. In fact, we have already passed the point at which there is enough $25/bbl oil supply to meet everyone’s desires. But production can still grow in this scenario, which is why it is “lite”. In that case, people may underestimate the significance of the problem.

Visualizing Peak Lite

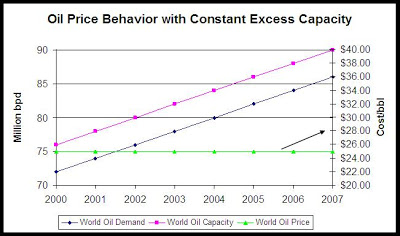

If excess capacity had not been eroded in the past 5 years, I believe the oil price would have remained around $25/bbl as shown in Figure 1. This figure is based upon the presumption that a constant 4 million bpd excess capacity existed from 2002-2007. That is enough excess capacity that even a fairly large disruption in supply can be managed by bringing excess capacity online.

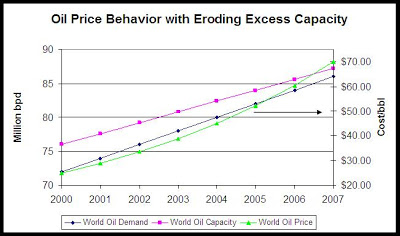

Figure 2 shows a more realistic picture of the behavior of the oil market over the past 5 years. As excess capacity has eroded, the price has risen and volatility (no volatility effects are simulated) has increased because any disruptions (or perceived disruptions) may be difficult to manage.

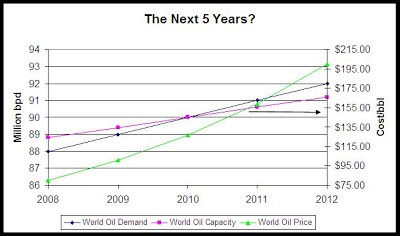

If current trends continue, Figure 3 may provide an indication of things to come, although I do expect the price rise to be incredibly volatile. I also think we will see periods of stability as demand is destroyed, but once the wealthier countries are the ones left bidding on the remaining oil, the price will likely increase dramatically.

Figure 3 shows demand exceeding supply in less than 5 years, although the exact timing is uncertain. And while some will argue that in economic terms demand can’t exceed supply, in real terms it can. If a man starves to death because he can’t afford food, does this mean that he did not demand food? No, he did demand food, but perhaps could not afford the supply at the market price. Many will find themselves in this position as prices increase, although demand for oil is admittedly more elastic than demand for food.

The IEA Endorsement

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has now endorsed the same general idea. In their July 2007 Medium-Term Oil Market Report (available for now here), they reach the conclusion of Peak Lite:

Despite four years of high oil prices, this report sees increasing market tightness beyond 2010, with OPEC spare capacity declining to minimal levels by 2012. A stronger demand outlook, together with project slippage and geopolitical problems has led to downward revisions of OPEC spare capacity by 2 mb/d in 2009. Despite an increase in biofuels production and a bunching of supply projects over the next few years, OPEC spare capacity is expected to remain relatively constrained before 2009 when slowing upstream capacity growth and accelerating non-OECD demand once more pull it down to uncomfortably low levels.

It is possible that the supply crunch could be deferred – but not by much. The demand side of this analysis is based on country-level GDP growth forecasts from the OECD and IMF, which amount to a global average of around 4.5% annually.

Lowering GDP growth to around 3.2% per year from 2008-2012 reduces annual oil demand growth from 2.2% to around 1.7% and the call on OPEC crude drops by around 2 mb/d by 2012. But this merely postpones by a year the point at which oil demand growth surpasses the growth in global oil capacity – in effect, delaying the return of minimal spare capacity by only a few years (unless the trend in upstream capacity growth changes).

They further note that it isn’t only the oil markets that look tight:

But the oil market cannot be looked at in isolation. Not only does oil look extremely tight in five years time, but this coincides with the prospects of even tighter natural gas markets at the turn of the decade. Over the past 25 years there has been substitution away from fuel oil and towards natural gas. However, when natural gas supplies have been insufficient or there have been supply problems (such as those seen following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, Russia in 2006), fuel oil has been the natural substitute. By the end of the decade, such flexibility may be constrained, producing upward pressures on all hydrocarbons.

The IEA suggests that current OPEC spare capacity is 2.50 million barrels per day, but this will dwindle by 1 million barrels per day by 2012. I believe the erosion of spare capacity we have seen since 2002, when oil was around $25/bbl, is primarily responsible for the price increase to the $70/bbl range. With several million barrels of spare capacity, there are many different producers that can bring capacity online in the event of a disruption. As that capacity erodes, there are fewer options for bringing on supplies if they are needed. The price creeps up, and volatility increases.

Whereas OPEC may not have been able to control prices in 2002 because there were too many suppliers to compensate for throttled production, in 2007 it is clear that other suppliers can no longer compensate for idled OPEC capacity. OPEC members have seen that as long as they maintain solidarity, they can maintain a floor price for crude oil (maintaining a ceiling is a different matter, as volatility in a tight market can push up prices much faster than they can react).

What to Expect

In the event of a worldwide peak in oil production, there won’t be enough oil to go around. Poorer countries will find themselves priced out of the market at various price points. The situation will be the same for Peak Lite, and this is what we have observed in the past 2-3 years. Many developed countries have seen their oil consumption rise over the past 2 years, even though world oil production growth has been flat to slightly negative. This means that demand destruction is occurring in some locations. I expect this trend to continue.

At the point that developed countries are bidding against each other for remaining supplies, the price of crude is likely to go much higher. Until now, demand has been moderated as poor countries in Africa and Asia are increasingly unable to afford $70/bbl oil. This price point is unlikely to significantly alter the demands of the United States, Europe, or Japan, which means that at some point of capacity erosion we could see oil prices quickly shoot past $100/bbl. While I think I will win my $1,000 bet on oil prices this year, I am not confident that the price won’t reach $100/bbl within 2 years.

To the extent that OPEC actually does have spare capacity, I expect them to continue to test the limits of what the world can withstand as far as oil prices go. If I managed their oil reserves, my goal would be to extract the highest possible price for the oil, but not so high as to trigger a global recession which would destroy demand and collapse the price. OPEC has gradually increased the price that they are satisfied with as they have seen that demand has remained strong at $50, $60, and finally $70/bbl oil. I expect them to continue to push this limit. By 2009, they may be suggesting $90/bbl as the price they are comfortable with.

The bottom line is that I believe the world has now reached the point at which the symptoms of peak oil are starting to manifest themselves – even though I still do not believe we have reached a true production peak. But, the consequences will be much the same as if we had.

I have been discussing this with friends for about a year now although I didn’t have the snazzy name of “peak-oil lite” for it.

I wholely agree with your conclusions except I think you have an optomistic view of the next five years. 🙂

I wholely agree with your conclusions except I think you have an optomistic view of the next five years.

I know a lot of people who really do think this, but I think price will be moderated as a large chunk of the world gets priced out of the market. The price climb will be pretty jagged, with fits and starts.

OPEC has gradually increased the price that they are satisfied with as they have seen that demand has remained strong at $50, $60, and finally $70/bbl oil.

OPEC would do well to remember that demand elasticity is non-linear and lagged. The first quadrupling of oil prices in 1973 had very little effect on demand. The later tripling in 1979 had a huge effect.

–doggydogworld

Actually, fossil crude consumption is falling in developed nations. Check out BP stats, on their website. OECD nations are consuming less fosil oil every year. I expect that trend to continue and deepen.

The IEA report also predicts that fossll crude demand will rise 2.2 percent annually, but mentions not price at all. The EIA says with high prices (more than $69) we will see 1.4 percent annually compounded growth in fossil demand.

Not much diff? Well, we end up with 3.5 mbd leftover in 2012 if EIA forecast is correct. No one talks about the EIA forecast.

The IEA also makes a strange prediction that biofuel growth will level off in 2009. That makes no sense.

My own guess is that world fossil oil demand, up just 0.7 percent last year, will stay at under 1 percent growth a year, at more than $60 a barrel, and perhaps go into decline. The good news is that radical reductions in demand from PHEVs are do-able. Meanwhile the Chinese, and Brit firm D1, are separately planting one million hectare jatropha plantations in Indonesia, while India is talking about millions and millions of hectares of the stuff.

A single one million hectare jatropha plantation might supply 2 days US oil consumption.

I think this oil shortage ends like all other shortages — with a glut. The longer OPEc draws out the string by cutting production, the longer the glut will last on the backside. Maybe 20 years, like the last shortage-then-glut.

But the next glut promises to have legs — new technologies, such as the PHEVs, and biofuels may extend the next glut for decades.

Actually, fossil crude consumption is falling in developed nations. Check out BP stats, on their website. OECD nations are consuming less fosil oil every year. I expect that trend to continue and deepen.

Consumption fell in 2006. One might expect that effect as prices raced much higher. But the overall trend is up. In the past 10 years, OECD consumption has increased by 2.5 million bpd, while world oil consumption has increased by 11 million bpd. Here are the numbers:

OECD Petroleum Consumption

I think we are going to continue to see the kind of squeeze we have seen since the price started to run up in 2002. And during that time – when oil prices went from the $20s in 2002 to the $70s in 2006, world oil consumption rose by over 6 million bpd. This is an increase of about 2% per year.

A single one million hectare jatropha plantation might supply 2 days US oil consumption.

I a working on some jatropha numbers right now. At first glance, I think it has real promise. (I am writing the renewable diesel chapter for a book on renewable energy, and I am covering jatropha at the moment).

Speaking of promise…

http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/technology/archives/2007/07/06/free_energy_erm_not_yet_says_steorn.html

That Steorn story is pretty funny. I can remember that a lot of people trotted their fantastic claims out. It’s like one of those links said: No matter how fantastic the claim, you can find some Ph.D., somewhere, to endorse it. And once you have the endorsement, it’s a story.

A great post, Robert, and why I’m a regular reader here. Keep up the good work.

In the event of a worldwide peak in oil production, there won’t be enough oil to go around. Poorer countries will find themselves priced out of the market at various price points. The situation will be the same for Peak Lite, and this is what we have observed in the past 2-3 years. Many developed countries have seen their oil consumption rise over the past 2 years, even though world oil production has been slightly negative. This means that demand destruction is occurring in some locations. I expect this trend to continue.

This is a dangerous misrepresentation of what is going on, Robert! As Ben Cole pointed out, much of the demand destruction was in OECD countries. The EIA report refers to this on Page 12 – calls it weather related. The report also shows that demand was destroyed in the former Soviet Union. I guess Putin can claim one success. Give him a few more years – he may yet completely destroy FSU demand.

The global economy makes things a lot more interconnected. As the report states, on page 15: By contrast, many emerging economies are often structurally energy intensive, being obliged to meet not only domestic demand growth but also the shortfall of heavy industrial activity observed in OECD countries. It can thus be argued that energy demand in emerging countries is partly fed by end-user demand in the OECD – as such, OECD countries are not necessarily becoming more energy efficient, but rather outsourcing their most energy-intensive industries to other countries.

So far from being a battle between us and them, we are all in this together. If demand is destroyed in China, the US will probably feel it as a sudden shortage of cheap products…

The report also makes an interesting point regarding the effect of price on demand: Nevertheless, prices remain an important determinant of oil demand. Indeed, current global oil demand is growing at about half the pace of a decade ago, despite a relatively similar economic performance, while crude prices have almost doubled in real terms. This price effect is more pronounced in mature economies than in non-OECD countries, partly due to the prevalence of controlled retail price regimes among the largest consumers (particularly China and Middle-Eastern countries).

Stay tuned.

I a working on some jatropha numbers right now. At first glance, I think it has real promise.

Anything that can get you excited has got to be good. Do share your thoughts at the earliest convenience…

There’s got to be a solution out there, as Special Agent Spooky Mulder might have said.

The IEA is an arm of the OECD, and makes alarmist pedictions, in an effort to goad OPEC into making oil investments and to boost output. OPEC ministers are asking the right q’s however: Why should we spend hundreds of billions of dollars to boost production and keep oil prices lower, especially when alternative fuels and conservation promise to wipe out much demand?

Back to IEA, how on earth do you project no increase in biofuels output after 2009?

Another intrsting stat: After the 1979 price hike, OECD oil demand fell, and did not recover 1979 levels until 1994 – a full 15 years! (BP stats)

This current price spike is not as severe (we would have to hit $100), but much better technologies and alternatives are out there now. Many EU nations mandating switching to biodiesel mixes, as is India. Sweden going to total independence.

People cry “Chindia” but India’s oil demand has, in fact been tepid. That leaves China. The big bomb, a few years out, is that China is spending mega-billions to develop its own fuel supplies, worldwide (they actually have an energy policy, as opposed to the Bu$h Administration). At some point, China will reap the benefits of its energy policy, and start leaving world oil markets (relatively speaking).

At more than $60 a barrel, we may see Peak Demand, but likely not Peak Oil. The next few years may tell, and certainly five-to-10 years. At more than $60 a barrel, there is historical experience to suggest fossil oil demand will go into a secular decline.

This is actually great news. We will be able to transition to a post fossil oil transportation system w/o recessions or worse.

The PHEVs, sipping biofuels mixes, wll extend the lives of commercial oil fields for generations.

The “bad news” is that a glut is likely, and a price plunge. Then the PHEVs will look like do-goody machines from the Jimmy Carter era. We go back to guzzlers.

from the original post:

To the extent that OPEC actually does have spare capacity, I expect them to continue to test the limits of what the world can withstand as far as oil prices go.

Robert, do you really believe that anyone in OPEC has any large amount of spare capacity (beyond the Saudis and Iraq)?

I’m of half a mind that they are WFO — max production.

I keep thinking back a few years, with the advertised price targets in the mid $20s — and OPEC couldn’t stop the cheatin’ then (well, other than the Saudis). Oil prices stayed down until demand caught up.

Then when oil prices started increasing, OPEC kept ratcheting up their target price and, it seems to me, pretending to be in control — making pronouncements about how $25 – $30 oil is a great level for world growth or whatever.

I’m not so sure that OPEC is along for anything other than a ride on the market — unable to control its own members’ supply, much less everyone else (2/3 of the world supply).

I just keep getting the mental image of a bunch of guys sitting in the front car of a roller-coaster ride. Sure, they’ve got a steering wheel, a gas pedal, and a brake pedal, but they aren’t attached to anything. Nonetheless, it is in their interest to *act* like they are making a difference.

Seriously — wouldn’t $40-50 oil be so much better for them in the long run? It’d quash those upstart sand-miners in Canada, make ethanol and other alternatives even less economically desirable. It’d also help fuel the growth in India and China, getting even more economies built from the ground up expecting liquid hydrocarbons.

What am I missing re:OPEC?

This is a dangerous misrepresentation of what is going on, Robert! As Ben Cole pointed out, much of the demand destruction was in OECD countries.

No. If you look at the data I linked to, you will see that OECD demand is relatively flat over the past 2 years (down 0.5%) and up 2.5% since 2002. Demand from China and India, on the other hand, has been on a steady climb, even in the past 2 years as world oil production has been flat and prices have increased to $70/bbl. What does this mean? It has to mean that demand has been destroyed, almost certainly in the poorest countries.

On jatropha, I would like to write something, but my hands are a bit tied. As I said, I am writing a book chapter on renewable diesel, and one of the stipulations is that I can’t have published these writings elsewhere. So, it’s either write 2 essays on jatropha (which I may do) or wait until the book comes out and then use bits of that.

What am I missing re:OPEC?

First, no, I don’t think they are sitting on spare capacity. (Russia may be able to ramp up their exports given time to invest some money). I certainly don’t think the Saudis – at the moment anyway – are sitting on the 2 million bpd that they claim to have in reserve. They might be able to develop that, given time, but I think right now they are pretty close to maxed out.

I think what has happened with OPEC is that they have figured out that they don’t have any competition, even at $70 oil. Previously, claims were made of economical shale oil at $40 oil, or that renewables would start to displace oil as oil prices climbed. That hasn’t happened, and I think OPEC knows that they are safe for now with $70 oil. And, as I said I expect them to continue to test that limit.

So, I don’t think $40 oil would be better for them. They have no competition as it is. Oil sands are not going to scale fast enough to hurt them, and if they do start to bite then OPEC can always open up the taps a bit. But at the moment, inventories around the world are high, and I think OPEC is trying to avoid opening up the taps now and crashing the price.

What does this mean? It has to mean that demand has been destroyed, almost certainly in the poorest countries.

Robert,

That would seem like a reasonable conslusion. Unfortunately it does not square with the facts. The chart on page 13 of the EIA report shows that between 1997 and 2002 demand increased in all areas, except the former Soviet Union. They also predict faster growth in non-OECD countries (charts p12).

Also, on page 16: Among non-OECD countries, the price effect becomes much more apparent when stripping out Chinese and Middle Eastern oil demand, which together account for roughly a third of total non-OECD consumption. Indeed, non-OECD oil demand ex China and the Middle East grew by 5.4% in 2004, but by only 2.7% in 2005 (the last year for which hard data are available) and by an estimated 2.2% in 2006. [Note growth is reduced, but still positive.] This halved pace of growth is mostly explained by the fact that most countries had no option but to let retail prices rise as administered regimes became fiscally unsustainable (e.g., in Thailand). As consumers became truly exposed to increases in international prices, oil product demand understandably slowed down. By contrast, the fact that demand accelerated over the past few years in China and the Middle East largely reflects the pervasiveness of capped retail prices, which have insulated consumers from price spikes, as well as booming economic growth, which has bolstered income per capita and hence energy use.

My take on it is this: the poor countries are already operating at a minimum oil consumption level. The guys with the ability to cut back, without hurting are the rich countries. (They are just going to bitch like hell!) The report agrees with this observation, as I have quote before: This price effect is more pronounced in mature economies than in non-OECD countries, partly due to the prevalence of controlled retail price regimes among the largest consumers (particularly China and Middle-Eastern countries).

However, the report also notes that: In fact, a more detailed analysis of the linkage between retail prices and transportation fuels in the US – as opposed to aggregated oil demand – suggests that recent price increases have actually had a limited influence on gasoline and diesel consumption, thus partially confirming the price inelasticity hypothesis (see “United States: Volatile Prices, Inelastic Demand”). Earth calling Ben Cole!

This would suggest for the hand-wringing about $3.00 – 3.50/gal, it will take much higher prices ($4-5/gal?) to actually curb demand. Man, this is perched to get interesting and probably, ugly…

Interesting post…similarly i found a report online that lists the companies and countries involved in the new russian oil production…

Russian Oil Production

Cheers!

Hmmm, sorry Robert, but the two graphs you present are inconsistent with each other!! The green line is supposed to be already higher than the others in the second graph if we are supposed to believe it generates from the first, as you suggest.

The green line is supposed to be already higher than the others in the second graph

The green line is going off the scale on the right, and that scale changed between graphs.