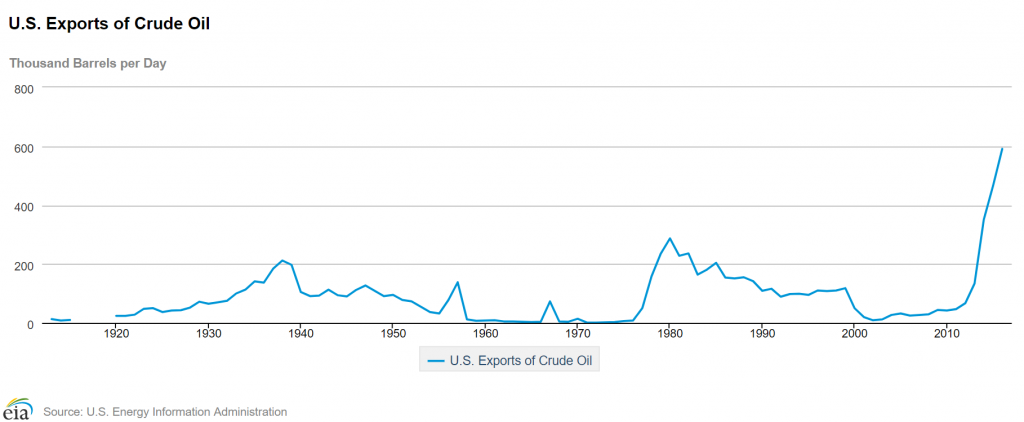

In the years leading up to the shale oil boom, crude oil exports from the U.S. were nearly nonexistent. There were two reasons for that.

First, following the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, a crude oil export ban had been enacted as part of an energy bill that aimed to mitigate future oil crises. The crude oil export ban restricted crude oil exports from the U.S. to all countries besides Canada.

But even if the ban hadn’t been in place, U.S. oil production severely declined for over three decades after 1970, even as U.S. crude oil consumption grew. So, over time, there simply wasn’t as much crude oil available for export. (I use that phrasing with the caveat that the U.S. has been a net importer of crude oil and petroleum products since 1949. More on that below).

As crude oil production in the U.S. surged, the dynamics began to change. Aided by the crude export ban, the longtime West Texas Intermediate (WTI) premium over internationally traded Brent crude vanished and WTI began trading at a discount.

U.S. crude oil producers had to sell their oil to U.S. refiners, who were happy to refine the discounted crude and then export the finished fuel products at full price (because the ban didn’t cover finished products).

Crude oil producers lobbied for an end to the export ban, and in late 2015 they got their wish when President Obama signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016. This $1.15 trillion spending bill contained a provision that stated: “To promote the efficient exploration, production, storage, supply, marketing, pricing, and regulation of energy resources, including fossil fuels, no official of the Federal Government shall impose or enforce any restriction on the export of crude oil.”

In 2016, the U.S. exported crude oil to nearly 30 countries. In 2017, monthly exports have exceeded one million barrels per day (BPD) on multiple occasions.

But the U.S. still imports about eight million BPD of crude oil. As a result, I am often asked why we are exporting oil at all. It comes down to the quality of the oil that is being produced, versus the kind of oil U.S. refineries are built to process.

Over the years, U.S. crude oil has gotten progressively heavier and sourer (meaning it contains larger hydrocarbon molecules as well as more sulfur.) Globally, heavy crude production increased in places like Canada, Venezuela and Nigeria. A wide price differential developed between heavy, sour crudes and light sweet crudes like WTI and Brent. Because crudes that are heavy and/or sour can produce about the same amount of finished products as lighter, sweeter crudes, refiners had a strong financial incentive to process the discounted crudes.

So U.S. refiners spent billions of dollars installing fluid catalytic crackers (FCCs), cokers, and hydrotreaters that are needed to process heavy sour crudes. After investing all of that money into processing the heavy crudes, the economics of running Bakken or Eagle Ford crudes in a heavy oil refinery are far less appealing than running a heavy Canadian or Venezuelan crude.

Heavy oil refiners would rather simply continue to import oil more suited to their needs, while the light, sweet crudes coming out of the U.S. shale plays are often a better fit for certain foreign refineries. Or, logistically it may simply be easier for Canada, for instance, to import U.S. crude for their East Coast refineries, while they export their heavy oil from Alberta to U.S. refineries that are equipped to process it.

In the next article, I will cover where the U.S. is currently exporting oil and finished products.

Follow Robert Rapier on Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.

Good explanation of the basics. Few comments I would add:

0. Interesting going back and looking at all the peak oilers who said we wouldn’t find any more light sweet. They knew about the tar sands. But assumed that was the only source of new oil. Now we have too much light sweet!

1. Heavy crude is still at a discount to light. Sometimes I hear peakers trying to say heavy oil is better. The reason it is better for a US refinery (with complex cracking, iso unit, coker, etc.) is that the crack spread is better. IOW, they want cheap heavy crude because they are built to handle it. You can actually still run a complex refinery on light crude. It would be interesting to see which they prefer with price equal. But I know some refineries that have basically decided to run a little lighter given the shrunk price difference in the US of the grades as well as the lower maintenance needed when running lighter slates. It’s not a nobrainer as you still have to make sure you don’t foam the tower (additives help though) and that you have adequate preheat.

2. The issue is not only the mismatch in quality versus refinery complexity but also complex geography (coasts, Rocky mountains, etc.) and the Jones Act (union shipping rules). It is literally cheaper to ship from the Gulf to foreign ports than to Atlantic ports.

3. A lot of stories look to the WTI-Brent spread but it is really the LLS to Brent spread to watch (this affects shipping). We have opened up a spread between WTI and LLS because of oil clogging into the middle of the country (DAPL dumping in southern IL, pipes south from Cushing running full again). There’s still an LLS to Brent spread to drive exports also. Just not as extreme as casual stories emphasizing Cushing to Brent pricing.