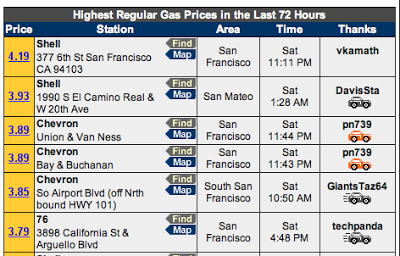

Gas Prices in San Francisco

We no longer have to talk about the possibility of $4 gasoline. It is here.

Thanks to Stuart Staniford for providing this picture. He lives in San Francisco, and said he drove past this station and saw the price for himself. It is going to be very interesting to see the inventory report from the EIA this week. How high do gas prices have to go before demand starts to drop? And will imports hit the shores in time to save the day, as they did at this time last year?

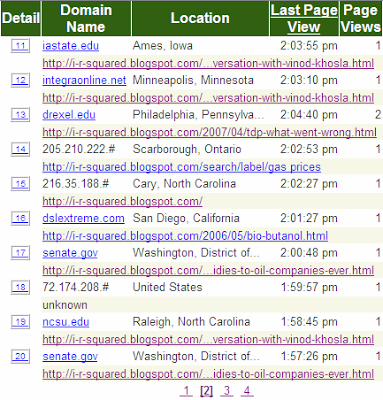

The Senate Stops By

Occasionally my Site Meter shows some very noteworthy domains, and last week I spotted 2 visits from the U.S. Senate at the same time. Probably staff members, I know, but when people that close to the policy-makers are reading your stuff, there is hope that the message is getting through.

On the next snapshot, I have the Senate (same as #20 above), the U.S. Army, the USDA, NC State, The University of Chicago, the Wisconsin State Government, another domain in D.C., and UC San Diego.

“How high do gas prices have to go before demand starts to drop?”

That is a good question. Are there any fresh studies on gasoline elasticity in the US? The ones I find when doing a search seem at least a couple of years old.

My own conversations with people (and observations of general habits) lately have led me to conclude that gasoline prices will have to go quite high for any substantial (doubt digit percentage) drop in gasoline consumption.

Hey! Don’t forget, you probably get more than a few NASA hits from me and others 🙂

Great Vinod Khosla info in the previous post — it’s bad enough that he’s funding the efforts in the first place, but now he’s trying to pull the wool over the eyes of more people.

I expect that people will pull money from discretionary expenditures before reducing gas consumption. I also expect people to dump low mpg vehicles (lmv) before significantly reducing miles traveled.

Look for reduction in revenue for businesses associated with rented experiences, high end foodstuffs, and non daily travel. I also expect a shift in the car market by August as the new model lmv’s sit and the hmv’s are in short supply.

there may be an uptick in scooter sales but that won’t last when people find it takes skill and training to ride 2 wheels vrs the 4 wheel ‘press the gas and go’

Are there any fresh studies on gasoline elasticity in the US? The ones I find when doing a search seem at least a couple of years old.

I haven’t seen a study, but I can tell you my observation. After Hurricane Katrina, when gas ran up to $3.00, it was a shock for many people. They suddenly cut back on their driving.

Then, after a while they became accustomed to the idea of $3 gasoline, so they started driving again just like they always had.

This winter we saw all-time record gasoline demand. What that tells me is that after the shock wore off, $3 gasoline didn’t really affect budgets enough to cause people to start seriously cutting back.

Cheers, Robert

gasoline elasticity in the US

I think it will show in housing sooner than usage. Most new single family dwelling housing in the U.S. is a longer commute than existing housing. Between the sub-prime mortgage problems and people thinking about a permanent longer commute with higher gas prices, the new housing market will probably cave and people will go on summer vacation trips rather than buying a new house.

I believe suburban housing will always be cheaper even accounting for higher gas prices. for example, in 1999, 250k bought 2000 sq feet and 0.75 acre in suburban boston. In cambridge the same 250k bought an 800 sq feet flat facing another apartment building. extrapolating, a 2000 ft flat would run in the area of a million dollars. a bit out of the reach of young families. I think many people would rather spend the money on gas and live in a nicer place

while it may seem a bit out of the domain of energy policy, I believe increasing energy costs will have a significant effect on our society. Take a look at:

http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/families_households/003118.html

from the summary above, I think change has started. family size is shrinking, age of marriage has risen 5 years over the past 30, numbers of never married is increasing significantly, and a host of other interesting tidbits.

I believe these trends are influenced by an uptick in urban living. I assert that if increasing energy costs drive people to urban living, we will see a significant increase in these trends. I suspect that energy costs may drive an increase in moves so you can be closer to work which in turn will drop stability of relationships and community involvement.

But before gloating too much over the dislocation higher gas costs will bring, I home people will think about what the second and third order effects might be because the future arrives way too soon and in the wrong order.

some energy influenced things to think about:

how do you bring food for a family of 4 home on public transport and up multiple floors? what if you both work? do you buy frozen foods?

how much will your food budget increase (time and money) (assume 1 local small grocer nearby and 1 megamart 30-60 min away by bus)

what will happen to the accident rate if people don’t drive every day but only rent occationally? will they keep their driving skills ?

how many nearby farm acres will be need to support bigger cities? (note: MA has been denuded twice to grow enough food for a much smaller population.)

how will we deal with the real estate distortions which will probably make housing and offices near public transport more expensive and poor people will be pushed into the shanties away from the city core.

how will crime change?

looking forward to your thoughts.

This (out of date) graph may be interesting vis-a-vis the question of how high prices need to get to change behaviour:

http://www.kantor.com/blog/gas.gif

The last trip above $2.50 got us a 12% drop in consumption. This time that doesn’t seem to be happening. Another interersting analysis (for which I cannot find the link) is to measure the price as a % of the average worker’s paycheck. Measured in those terms gasoline is still very cheap by historical standards, even at $4/gallon.

http://measuringworth.com/calculators/uscompare/

The above link has some of the data I was referring to, though, unlike the study I cannot find, it doesn’t go back to the early 20th century. Still, it’s interesting to look at the different ways in which you can “cost” it: there are at least two different ways to adjust for inflation (CPI and GDP deflator), then there’s %-of-GDP as a metric, and then there’s %-of-unskilled-wage as a metric. For example in 1949 (the earliest year in this series), gas was nominally 27 cents per gallon. That’s the equivalent of $1.85-$2.21 today, depending on your preferred inflation metric. However, the price would have to reach $3.75 to exact the same toll on the wage of an unskilled worker, and $6.32 to have the same effect on per-capita GDP. Clearly, prices have to go much higher before behaviour (other than grousing) will really change.

Here is a comment that a reader tried to post, couldn’t because of a technical glitch, and e-mailed to to me. Not sure whether he intended to use his real name, so I will omit it:

——————-

One obvious answer to “How high do gas prices have to go before demand starts to drop?” is – quasi-infinite.

If people get the idea that the price is going to drift upward indefinitely, they may decide to buy now, to go on that long-distance vacation, while they still can. This is what happened with inflation in the 1970s – no sense saving or holding onto money if it’s going to become worthless anyhow.

N.B. this is probably one of the great unstated reasons – an elephant in the room – why baby-boomers don’t save. It was a bootless exercise in their formative years. The exclusive Fed focus on “core inflation”, i.e. everything except what’s rising, surely can’t be giving anyone warm fuzzies.