The dramatic events over the weekend in Venezuela have renewed global attention on a country that, on paper, should be one of the world’s great energy powers. Venezuela holds the largest proven oil reserves on Earth, yet its oil industry has been in long-term decline for two decades. Understanding why requires looking past the headlines and into the technical, legal, and political decisions that steadily dismantled what was once a cornerstone of the global petroleum system.

The United States confirmed that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is now in U.S. custody following a military operation inside Venezuela. President Trump announced the operation publicly, and Vice President JD Vance said the administration had offered “multiple off ramps,” but maintained two firm conditions: that drug trafficking must stop, and that what he described as “stolen oil” must be returned to the United States.

That final phrase—stolen oil—points to a long-running and deeply consequential dispute over Venezuela’s oil industry, one that helps explain why a country with the world’s largest crude reserves has spent more than a decade in economic collapse, and why energy remains central to its geopolitical importance.

The World’s Largest Oil Reserves — On Paper

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, Venezuela holds roughly 303 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves, the largest total of any country in the world.

But that headline figure obscures a critical reality: most of Venezuela’s oil is ultra-heavy crude, concentrated in the Orinoco Belt. Unlike light, sweet crude produced in places like the Permian Basin, Orinoco crude is dense, viscous, and difficult to move. Producing it at scale requires heating, dilution with lighter hydrocarbons, and upgrading in specialized facilities before it can be refined. The extra level of processing also means it requires higher oil prices to be economical.

For decades, Venezuela relied on partnerships with U.S. and European oil companies to provide the technology, capital, and operational expertise required to make that system work. Those partnerships would not survive the 2000s.

Expropriation And The Unraveling Of PDVSA

While Venezuela formally nationalized its oil industry in the 1970s, beginning in the early 2000s under President Hugo Chávez, Venezuela moved beyond its earlier state ownership model and launched a wave of expropriations that fundamentally reshaped its oil sector. Foreign operators were forced into minority positions alongside Venezuela’s national oil company, PDVSA, or saw assets seized outright. Major U.S. firms, including ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, ultimately exited the country and pursued international arbitration over uncompensated takings.

International tribunals later awarded billions of dollars in compensation to foreign companies—awards Venezuela has largely failed to satisfy. This period marks the origin of the “stolen oil” language now resurfacing in U.S. political messaging.

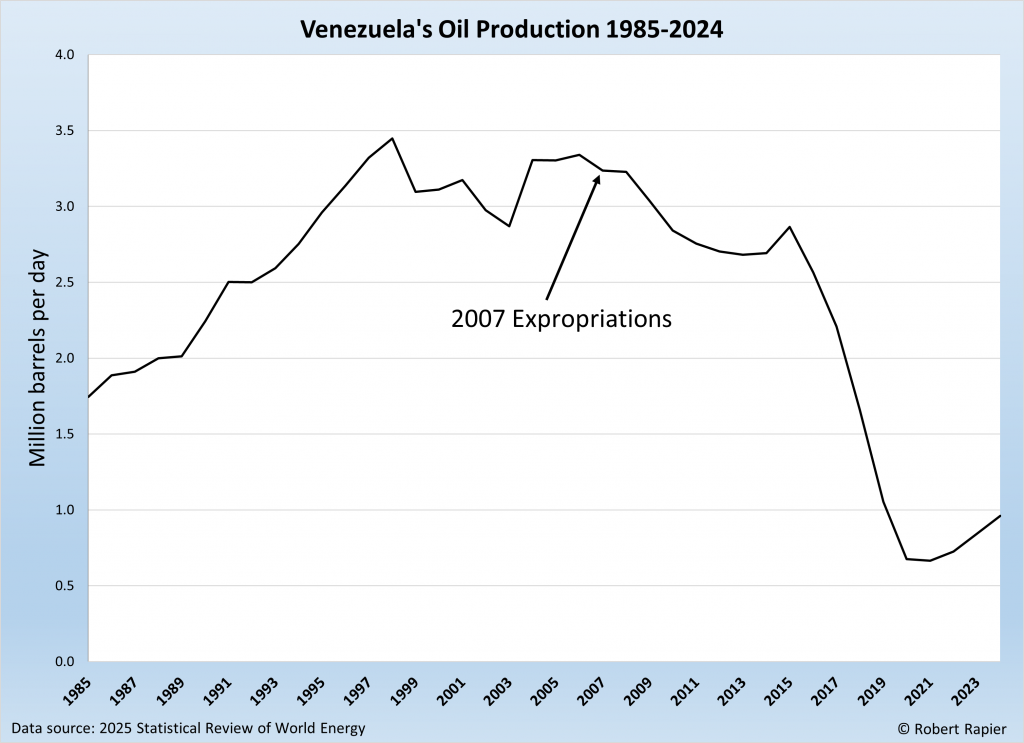

The consequences for Venezuela’s oil industry were severe. PDVSA lost access to foreign capital and technical support. Skilled engineers left the country. Upgraders and pipelines fell into disrepair. Production declined steadily, falling from more than 3 million barrels per day before the expropriation to under 1 million bpd in recent years.

By the time Maduro assumed office in 2013, the industry was already in structural decline. Corruption, mismanagement, and U.S. sanctions under his tenure further constrained output and exports.

Why Heavy Oil Requires Foreign Expertise

Maintaining production of heavy oil requires constant reinvestment, reliable power, and uninterrupted access to diluents—many of which historically came from the U.S. Gulf Coast. Without these inputs, and high enough oil prices to support them, production systems fail quickly.

When foreign partners exited Venezuela, PDVSA lost the ability to sustain that complex ecosystem. Steam-assisted extraction stalled. Upgrading capacity deteriorated. Fields that required continuous maintenance were left idle. Even when oil prices recovered globally, Venezuela was unable to capitalize.

This is the paradox at the heart of Venezuela’s energy crisis: the country with the world’s largest oil reserves lacks the operational capacity to turn those reserves into stable production without outside help.

Oil, Sanctions, And The U.S. Perspective

U.S. officials have long argued that Venezuela’s oil sector became intertwined with sanctions evasion, illicit shipping networks, and criminal activity. In recent years, Venezuelan crude exports increasingly moved through intermediaries and foreign buyers operating under sanctions pressure.

Vice President Vance’s statement reflects the administration’s view that oil revenues were central not only to Venezuela’s economy, but also to sustaining the Maduro government despite international isolation. Whether one agrees with that framing or not, it underscores why energy issues remain inseparable from broader U.S.–Venezuela relations.

What Comes Next For Venezuela’s Oil Sector

With Maduro now reportedly in U.S. custody, Venezuela’s oil future enters a period of profound uncertainty. Several outcomes are possible.

A transitional government could seek to re-engage foreign operators, reopen arbitration discussions, and rebuild contractual frameworks to attract capital. U.S. companies with outstanding claims may pursue compensation or negotiated re-entry. China and Russia, both of which hold significant oil-backed interests in Venezuela, will likely seek to protect their positions.

What is unlikely is a rapid recovery. Even under favorable political conditions, restoring Venezuela’s oil production would take years. Upgraders must be rebuilt, infrastructure modernized, and human capital restored. Heavy oil does not rebound quickly, especially when oil prices are depressed.

The Bottom Line

Maduro’s capture represents a major geopolitical escalation, but the underlying story is not new. Venezuela’s crisis did not begin with sanctions or military action. It began when a technically complex oil industry was stripped of the partnerships and investment required to function.

Venezuela’s vast oil reserves remain real, but reserves alone do not produce prosperity. Without technology, capital, expertise, and a sufficiently high oil price, the oil stays in the ground. That reality has shaped Venezuela’s economic collapse, its international disputes, and the central role oil continues to play in the current events unfolding there.

Follow Robert Rapier on LinkedIn or Facebook